In 88 BC, a conquering king, Mithridates of Pontus — one of Rome’s greatest enemies — swept through Asia Minor toward Pergamon.

His campaign took a gruesome turn when he massacred 80,000 Roman and Italian settlers in several Anatolian cities as retribution for an invasion of his kingdom the previous year.

It was a brutal act of defiance designed to send an unmistakable message: Rome wasn’t welcome.

Mithridates wasn’t just a warrior; he was a showman with a taste for spectacle. He melted down the available silver and gold, summoned the Roman governor of Pergamon, and executed him in the most dramatic way imaginable: pouring molten metal down his throat.

The governor, quite literally, “choked to death on gold.”

Greed and provincial unrest marked just the beginning of the end for the Republic. By the first century BC, Rome and its republican ideals were giving way to corruption, social unrest, and autocratic rule.

Ambitious generals, ending with Julius Ceasar, were dismantling the very institutions that had held the Republic together for nearly 500 years. The fall of Rome wasn’t a sudden collapse — it was a slow, messy unravelling.

So, what caused a representative democracy to crumble after half a millennium? And what lessons does its downfall hold for us today?

Greed

How do you govern a territory that covered approximately 1.5 million square kilometres (579,000 square miles) by the late 1st century BC?

This was the challenge the Roman Republic faced when cracks started forming in its network of millions of subjects.

Typically, Roman-controlled regions were given “nominal autonomy” to allow the republic to avoid direct control over conquered territories, preferring to operate them at arm's length. This would often result in appointing a local figurehead to create a sense of normality for the subjects and lower the republic's administrative costs.

How did they impose their power on the outer provinces across such a vast expanse?

Intimidation — of course.

If the regions did not comply with Roman rule, the republic quickly resolved such disorder with swift military action, followed by the crippling of their military or the promotion of new puppet leaders that “would jump whenever the Romans snapped their fingers.”

As long as the outer regions of the Republic remained in line, the Romans were content with a “delicate balance between exploitation and disengagement.”

Nothing is a better example of that than the Republic’s acquisition of the Greek city-state of Pergamum, now Western Turkey. The province was left to the Romans by its last king in his will. This ignited fierce debate in Rome about managing the city with “riches beyond even the Romans’ plunder-sated dreams”.

For a long time, the Republic had a policy of war and looting. Pergamum posed a different way of doing things as the region benefited from organised taxation, which served as a “glittering opportunity” for the Republic to learn from its far older eastern neighbours.

Earlier in Roman history, taxation centred more on funding military campaigns aimed at wealthy landowners. Poorer Citizen’s were generally exempt. Provinces, including Pergamum, loomed as a “honeypot” primed for exploitation, propelling Roman wealth into overdrive.

These taxes on conquered provinces came in the form of stipendium (a fixed tribute) and later, under the Roman governors, various forms of vectigalia (regular taxes), including land taxes and trade taxes. Local authorities initially collected provincial taxation but were later managed by Roman officials or contractors called publicani.

These private tax collectors bid for the right to collect taxes in specific provinces. The “tax farming contracts” were publicly auctioned, and the“Tribute” was paid in advance to the state.

Given the expense associated with these contracts, only the wealthy, often in groups, could afford to participate. They were a form of ancient corporation.

Historian Tom Holland summarised the phenomenon:

“Highways originally built as instruments of war, now served to bring the taxman faster to their victim.”

The publicani blatantly extorted the people of Pergamum and other Roman provinces. Senatorial commissioners administering the region were as corrupt as the private corporations collecting the unfair taxes. How low were these publicans regarded? The Bible offers a unique insight into their societal position. Matthew 9:10–11:

“While Jesus was having dinner at Matthew’s house, many tax collectors and sinners came and ate with him and his disciples. When the Pharisees saw this, they asked his disciples, ‘Why does your teacher eat with tax collectors and sinners?’”

Rome had a new way of asserting its power. Holland would go on to say that“Cities were no longer sacked, they were bled to death instead.”

This left Asia Minor open to a form of liberation. Mithridates capitalised on the disharmony in the Greek cities created by Roman oppression, rallying widespread support among those frustrated by unfair Roman rule.

His massacre, known as ‘Asiatic Vesper’, of 80,000 Roman and Italian residents during his campaign signalled his defiance. Rome would respond. General Lucius Sulla launched a counter-campaign, defeating Mithridates’ forces and forcing him to withdraw from Greece and Asia Minor.

By 85 BC, an uneasy and short peace had been reached, with Mithridates retaining his crown but paying a significant indemnity to Rome.

Fear & oppression could only be used as a weapon in the provinces for so long, inadvertently inviting ‘barbarians’ into its territories. Self-serving & corrupt individuals were the primary benefactors of the Republic’s immense power, leaving Holland to summarise that “Roman probity was a sick joke.”

This behaviour allowed warlords to restore order abroad and at home, becoming one of the pillars of the Republic's downfall.

Roman greed planted the seeds of unrest & autocratic rule.

Class Division

Social hierarchy formed the bedrock of Roman society.

Since the formation of the Republic, the people were divided between Patricians, descendants of Rome’s founding families, and Plebeians, the broader free population — farmers, labourers, and artisans.

Over time, the patricians took control of the land and wealth, consolidating their power through laws. The disenfranchised plebeians became subservient to the patricians, often indebted to the aristocratic class and forced into servitude if they could not repay.

During the birth of the Republic, the people had risen to free themselves from Tarquin, the last king of Rome, and establish new governance. By the later stages of the Republic, the plebeians had found themselves just as “tyrannised by the ancient aristocracy of Rome … as they had ever been by the kings.”

They would fight back.

The class inequality led to the Conflict of the Orders (494–287 BCE), a prolonged struggle during which plebeians demanded greater political representation and protection. They achieved significant milestones, such as the creation of the Tribunes of the Plebs, who could veto patrician legislation, and the Twelve Tables, which codified Roman law and provided some legal equality.

Enter the Gracchi brothers. Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus championed the cause of the plebeians during the later stages of the Republic.

Tribunes a decade apart, they sought to address Rome’s growing inequality. In 133 BC, Tiberius proposed redistributing public land to landless citizens, bypassing the Senate to push his reforms through the Assembly — a bold breach of tradition that enraged the senatorial elite. His controversial bid for re-election as tribune led to his assassination by a mob of senators.

A decade later, Gaius built on his brother’s momentum, advocating for grain subsidies, expanded citizenship, and reducing the Senate’s influence by empowering the equestrian class (wealthy landowners ranking below senators). His reforms deeply polarised Roman politics, and like his brother, he faced violent resistance, ultimately dying during a Senate-led crackdown.

The Gracchi brothers’ reforms highlighted the deep inequalities within Roman society, stirring unrest among the elite and the ordinary citizens. Their actions not only set a precedent for bypassing senatorial authority, but as Holland explains, “the fate of the Gracchi had conclusively proved that any attempt to impose root and branch reform on the Republic would be interpreted as tyranny.”

This deepening instability laid the groundwork for the Social War (91–88 BC) that would engulf the Italian peninsula in the first century BC. It erupted when Rome’s Italian allies revolted, frustrated by their lack of Roman citizenship despite bearing much of the burden of military service. The allies formed their own confederation with a senate and coins, challenging Roman authority.

Rome eventually suppressed the rebellion, but only after granting citizenship to the Italian allies through the Lex Julia and subsequent laws, integrating them more fully into the Roman political system. This expansion of citizenship shifted the balance of power within the Republic, straining its political institutions and contributing to the weakening of the Senate’s influence.

The Gracchi brothers’ deaths illustrated how violence was becoming an accepted political too. The integration of new citizens disrupted traditional voting blocs. It heightened existing class tensions, leaving powerful generals the opportunity to leverage these divisions for personal gain, further eroding the Republican system.

Autocratic Rule & Factionalism

History would be nothing without people of action. The late Republic is a perfect example of this behaviour.

As the fabric of Roman society started to fray at the seams, opportunistic generals took advantage of their position of power. Military reforms allowed soldiers to be recruited from the landless poor, and the legions increasingly became more loyal to their generals than the Republic itself.

This shift in allegiances allowed ambitious leaders like:

Gaius Marius

Lucius Sulla

Pompey the Great

Julius Ceasar

… to leverage their armies for political power. Marius and Sulla’s conflict perfectly epitomises the changing landscape.

Sulla initially served under Marius during the Jugurthine War (112–105 BC), during which Sulla’s daring capture of King Jugurtha brought him recognition. Though this success contributed to Marius’s victory, it also sparked jealousy and rivalry between the two men.

Their relationship deteriorated further during the Social War, in which both generals played critical roles in suppressing Rome’s Italian allies. Despite Marius’s earlier successes, his influence waned as Sulla’s star rose when he took command of the Roman forces against Mithridates in 88 BC.

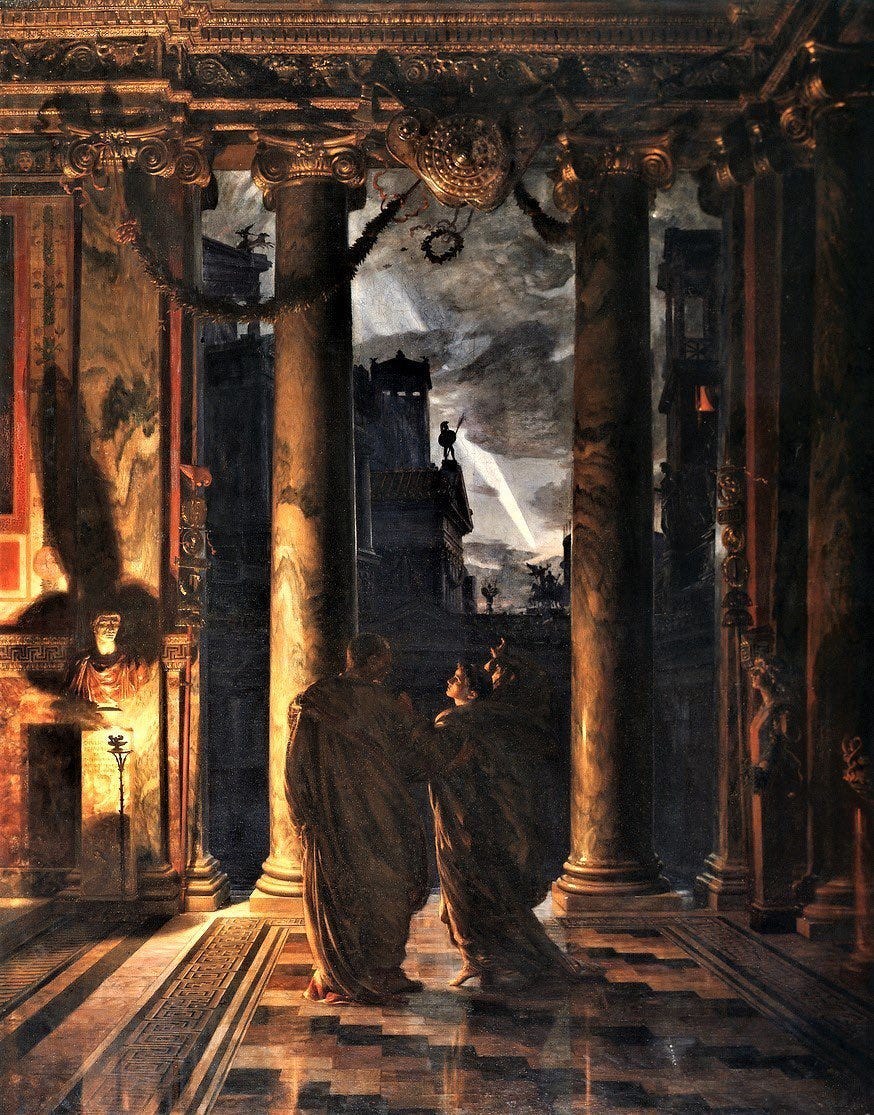

The tipping point came when Marius, seeking to reclaim his authority, supported a coup to transfer Sulla’s command to himself. In response, Sulla did the unthinkable — he marched his army on Rome, an unprecedented act in Roman history.

Sulla seized the city and secured his command. Marius & the Senate, short of military support in the city, could do nothing to stop Sulla’s bold action.

… naturally, having taken this fateful step, Sulla was desperate to force his advantage home. Summoning the Senate, he demanded that his opponents be branded enemies of the state. The Senate, with one nervous eye on Sulla’s guards, hurriedly obeyed.

Marius fled Rome but later returned with his forces, which led to violent reprisals and political purges by both factions. The animosity between Marius and Sulla set the stage for Rome’s descent into multiple rounds of civil war, which ended with Caesar’s famed dictatorship.

By the time Caesar crossed the Rubicon and marched on Rome 39 years later, he was merely following a trend of behaviours set by his predecessors. He took the final step and shamelessly seized complete power as dictator perpetuo – dictator for life.

The Senate’s loss of power and influence during the late Roman Republic was marked by its inability to contain these ambitious men. These figures rose to prominence by exploiting Rome’s political and military systems, often bypassing or undermining the Senate.

Marius set a precedent with his military reforms, while Sulla brazenly marched on Rome. Pompey further exposed their weakness by accumulating extraordinary commands and ignoring traditional checks on power. The Senate’s greatest failure came with Caesar.

Despite clearly violating Roman law in crossing the Rubicon with his army, the Senate hesitated to act, paralysed by division and fear. Their passivity, born of internal conflicts and a fear of alienating powerful allies, ultimately paved the way for autocracy. Caesar’s actions left the Senate “stupefied.”

His ascension to power was not a sudden coup but the culmination of a long process of senatorial inaction and missteps.

A citizen-led government is meaningless if it can’t be defended. The Republic’s failure to adapt left its institutions dangerously exposed to various strong men, each slowly eroding the political framework piece by piece.

Will We Learn From Rome’s Failure?

This is my take on the Republic’s fall, backed up by my understanding of some of Historian Tom Holland’s many points.

It’s a subject that can (and should) be debated endlessly.

Political representation of the people has long been the bedrock of democracy. But today, can we say that we feel heard? If modern governance fails to meet people’s expectations, it may lead to unpredictable and dangerous times.

The Roman Republic is an everlasting testament to what can go wrong when greed and self-interest reign. Sound familiar?

Multi-national corporations avoiding fair taxation

Big Pharma prioritising profits over people

Working-class families struggling with rising costs and stagnant wages.

These patterns have proven to have consequences. Are we sitting on a ticking time bomb? That remains to be seen.

We must be diligent about these issues to prevent history from repeating itself. How? That's outside this writer's pay grade. But I know we can learn from our past… if we choose to listen.

Roman history, rich in event and drama as it is, will always possess something of the quality of the very best science fiction: the narrative of a world that can seem, on occasion, as unsettlingly familiar as it is strange. — Tom Holland

Ignited by History is for curious people like you!

You can subscribe to my Substack for free to receive my next post directly in your inbox. Please share this with a friend who’s also lost sleep over something that happened hundreds of years ago…

References

Holland, Tom. Rubicon. United Kingdom, Little, Brown Book Group, 2011.