It's important to forgive. It's drummed into us from an early age. This may come easier to you than others, or perhaps you remember every insult you have received. Whatever the case, we all know the significance of forgiveness.

This doesn't make it easy.

Some experiences are too painful to forget.

My great-uncle, affectionately known as Roger, set out in October of 1992, attempting to retrace such an experience. Despite some hesitation, Roger returned to the "scene of three and half years of misery" and revisited his P.O.W. camp in Macassar 50 years after his release.

As he set out, he decided to write along the way as he was "possibly the only P.O.M. in the position to do so."

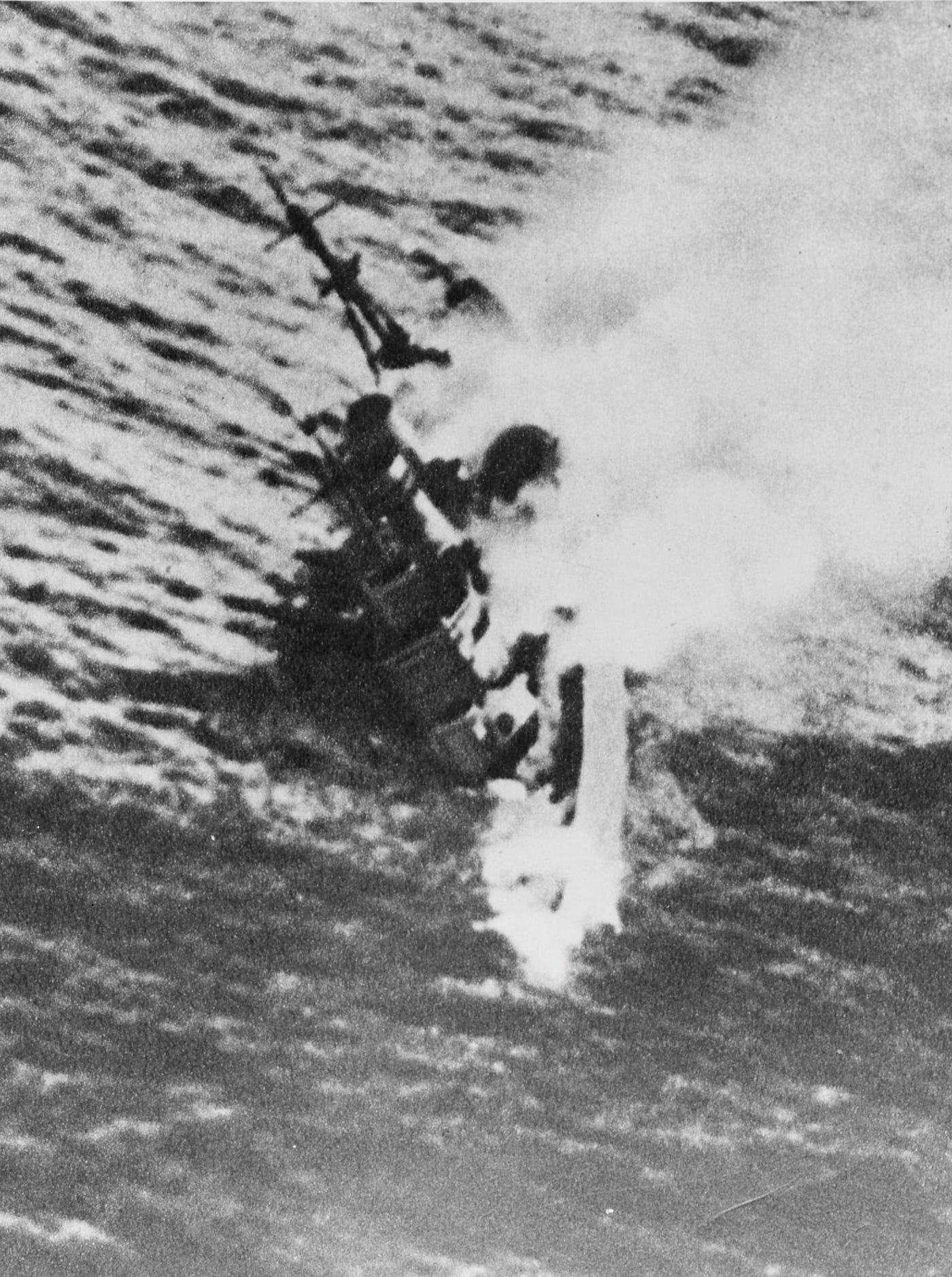

On the 1st of March 1942, H.M.S. Encounter was heavily damaged in the Second Battle of the Java Sea, resulting in the ship being scuttled and 149 men, including Roger, forced overboard into the water.

"After the initial exchange of gunfire (they were hopeless), the Japanese saturated our fleet with torpedoes, and our whole fleet was eventually sunk," Roger writes in his travel log. "I was in the water for 24 hours and was eventually picked up by a Japanese destroyer and taken to Macassar."

"Many of my mates drowned themselves rather than be taken prisoner of war."

"I took the chance."

This story will revisit the events leading up to my great-uncle's capture, review his notes about his time as "a guest of the Japanese," and help us view forgiveness through an unimaginable lens.

Second Battle of the Java Sea & Roger's Capture

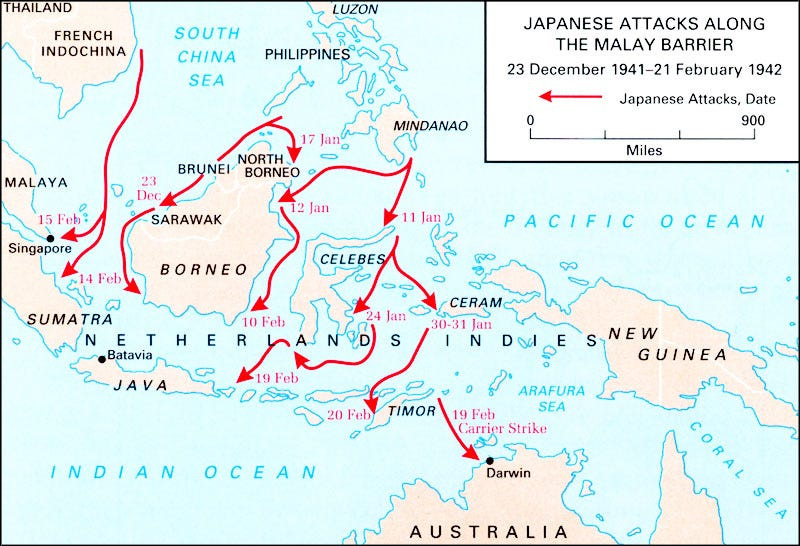

The Second Battle of the Java Sea took place on March 1, 1942, as part of the larger Japanese offensive to seize control of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) during the height of WWII.

Japan's race to control the region followed its attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. With military operations escalating, Japan looked to control the vital oil-rich region of the Dutch East Indies and other resources, including rubber and tin. Japan had limited natural resources on its islands and relied heavily on imports, particularly oil, to sustain its military and industrial activities.

Additionally, the region held strategic interest for the Japanese Empire as it was important for them to control the sea routes and maintain supply lines throughout Southeast Asia, weakening the Allied military presence in the Pacific and establishing a defensive perimeter for their homeland.

Hostilities erupted in the region as Allied forces sought to unify and resist the southward advance of the Japanese toward Australia. This effort led to the formation of a combined Allied fleet of American, British, Dutch, and Australian (ABDA) vessels tasked with defending Java.

In late February, Rear Admiral Karel Doorman’s Eastern Strike Force encountered the approaching Japanese fleet in the Java Sea. During the ensuing battle, Doorman launched persistent attacks against the Japanese but could not stop their progress. The engagement resulted in the loss of the light cruisers HNLMS De Ruyter and Java, along with the death of Doorman himself.

After the initial loss, Allied ships were scattered and in retreat. The Japanese aimed to destroy any remaining Allied ships to ensure complete control over the Dutch East Indies.

Among the retreating forces was Roger & the ship in which he served, H.M.S. Encounter. "We had to stop them somewhere to prevent an eventual landing on Australian Shores," Roger recounted in his travel log. Years later, the significance of his mission was still clear, but by this point in the battle, H.M.S. Encounter and the Allied forces had lost all hope of achieving their objectives.

A desperate race to escape was on.

The Japanese, led by Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi, consisted of cruisers and destroyers who had already proven superior in the previous engagement. They aimed to intercept and eliminate Allied naval resistance, which was still on the move.

On the morning of March 1, British heavy cruiser H.M.S. Exeter and two destroyers — H.M.S. Encounter and the American destroyer U.S.S. Pope — attempted to escape southward toward the Indian Ocean. The already damaged Exeter was the first to be intercepted and fell under heavy Japanese fire.

The ship was critically damaged, leading to its sinking.

The two accompanying destroyers, Encounter and Pope, also came under attack.

Encounter was sunk after an attempt to lay a smoke screen for the immobilised Exeter, while Pope tried to escape but was eventually hunted down and sunk by Japanese aircraft later that day.

An estimated 652 (Exeter) and 149 (Encounter) sailors found themselves stranded at sea.

The Encounter survivors were adrift for some 20 hours in rafts and lifejackets or clinging to floats. Many were coated in oil and unable to see. Eventually, and somewhat surprisingly, the Japanese destroyer Ikazuchi transitioned into a humanitarian mode and began rescuing survivors.

This move was not without risk, as the Japanese would have been wary of potential submarine attacks. Yet, their commander, Shunsaku Kudo, decided bravely to return to the men in the water — a rare move for Japanese forces during WWII.

"That fine officer searched for survivors all day," Sam Falle reported about Commander Kudo. "Stopping to pick up even single men, until his small ship was overflowing."

Felle was a fellow Encounter survivor, an eventual British diplomat post-WWII, and the author of My Lucky Life, an autobiography in which he recounted his rescue.

“An awning was spread over the fo’c’s’le to protect us from the sun; lavatories were rigged outboard; cigarettes were handed out; and by a biblical type of miracle, our hosts managed to give all 300 of us food and drink…. The Japanese did not know, it seems, that there were no English submarines in the Java Sea. Yet they had continually stopped to rescue every survivor they could find.”

This description of their rescue provides a small window into Roger's first moments after being pulled from the water. Falle would later seek out Commander Kudo's grave in 2008 to show his respects to the man who saved his life, and surprisingly, his family only learned of his actions on Falle's arrival.

The battle resulted in a decisive Japanese victory. The destruction of the Exeter, Encounter, and Pope marked the end of significant Allied naval resistance in the region. The Dutch East Indies soon fell into Japanese hands, giving Japan control over vital resources.

The remaining survivors were shipped to Macassar (Makassar) and imprisoned.

Roger would sombrely write in the skies above the Java sea while returning to Macassar in 1992, "I got a little emotional thinking of my shipmates whose bones will lay upon the sea bed forever."

Time in Captivity & Return Trip

Fifty years after his release, Roger arrived in Macassar.

After speaking with a local doctor friend who had completed a few trips to the area, he decided to make the journey himself. On the top of his agenda was to inspect the war graves of the friends he lost in captivity.

Upon arrival, he spent time locating the prison camp, docks, and "other places where we used to slave our guts out."

He had questioned the doctor about the condition of the graves, and he had assured him they were "well cared for." Unfortunately, Roger realised that his friend had confused the prisoner-of-war graveyard with the local military cemetery.

Roger was furious and emotional when he located the correct graveyard, recording that the Japanese kept no burial records and "could not find a British name anywhere."

Dismayed by the situation, he sought an explanation from someone of a similar age. Luckily, he located a man of "some official capacity" who explained that the P.O.W.s were buried in the area but were recovered by "various nationalities" after the war.

Those not claimed were buried in a communal grave where Roger stood.

“The grave is about 6 metres square high with a centre pole that looks very much like a periscope. I somehow knew that this was the spot where Bogey Knight and Buster Browne were resting.”

Overwhelmed with emotion, Roger placed three posies on the wall nearby and "said a few words" to the friends he had lost.

It is difficult to grasp Roger's time in captivity. Like many men who survived the ordeals of these camps, he chose to keep his experiences to himself.

As a curious teenager, I used to ask my grandmother about his time as a prisoner, and she would often shrug and explain she had very few details to tell. She did have one small piece of information — the Japanese guards had a cruel habit of putting out their cigarettes on the bare backs of the prisoners.

It was the only experience that Roger was willing to share with his sister.

It wasn't until I discovered Roger's travel log, recorded in 1992, that I got a rare insight into his daily life as a prisoner of war. In it, he humorously explains the tasks the Japanese enforced on the men. In one summary, he details the manual labour of creating a new rail line.

"There is still no railway here," Roger recalls.

“The Japanese tried to start one from Macassar to the north, but the stupid buggers made sleepers and bridges from coconut tree timber — lasts about three months before rotting and the effort was eventually abandoned — after all our work in that bloody heat with no tucker.”

In another entry, he explains how the Japanese must have been short of steel for the war effort as "places they occupied were stripped of any steel."

It was the prisoner's job to dig up old Dutch oil storage tanks that had been intentionally destroyed by fire years earlier and instructed to "knock off the rivet heads and separate the steel plates." Roger would say there were "millions" of them and that the "clanging noise was unbearable."

"What a job!" Roger sarcastically summarised.

In a sign that the men were not losing their sense of cheek, they developed a plan to avoid the unending manual labour.

It would take the armed guard ten minutes to patrol right around the tank, so when he could see you, you swung those hammers like billy-oh, or you got a belting. Once he was out of sight we would all sit down, roughly six to a group, and one of us would just drop a hammer on to the plates occasionally to keep the noise going. They never woke up to this.

It was a risky game they were playing as the Japanese didn't take well to insubordination.

When Roger lamented his difficulty forgiving his captors, he told a story about an Australian digger who would not "kow tow" to the Japanese. This particular soldier told them to "get f — -d," and as a result, the Japanese "dragged him away”. As he was being removed, he shouted to his fellow Aussies to "Mark these bastards down for future reference”.

They beheaded him for his disobedience.

Room for Forgiveness?

After 50 years, Roger's return to Macassar was not just symbolic — it was a bittersweet trip that refreshed memories of friendship, suffering and survival. Despite the passage of time, the psychological wounds of captivity remained open.

His journal entries reveal a man shaped by anger, unable to reconcile the trauma he carried. "My anger is boundless," he wrote, reflecting on the suffering inflicted on already half-starved men. But what struck me most was not just the depth of his pain—it was the realisation that there was no room for forgiveness in Roger's heart.

Could forgiveness have given him peace? It's difficult to say. For Roger and for many who have endured unimaginable hardship, forgiveness might seem impossible — perhaps even unjust. "I'm not a hating man," wrote Roger when summarising his conflicting emotions, but at the same time, he chose to cite the Japanese treatment of the Chinese at Nanking in 1939 when concluding his journal — "Tied thousands of captives to stakes for bayonet practice. A fact."

When he combined his personal experiences with his knowledge of Japanese conduct throughout the war, his anger hardened and became permanent.

I challenged myself to read and re-read his journal without judgment. This is how he felt after significant trauma. After experiencing torturous conditions, losing friends, and being reminded by his captors that they were "the chosen race."

Roger’s mind was understandably set. But could he have received peace if he had been more open-minded? If he had focused more on the stories that humanised his enemies, such as the example of Commander Kudo.

Maybe we ask too much of Roger — or ourselves? Can we hold both anger and forgiveness in our hearts at the same time?

This complexity is best expressed by Bishop Desmond Tutu and his reconciliation efforts in post-apartheid South Africa:

“Forgiving is not forgetting; its actually remembering — remembering and not using your right to hit back. It’s a second chance for a new beginning. And the remembering part is particularly important. Especially if you don’t want to repeat what happened.”

The 1984 Nobel Peace Prize recipient reminds us of restorative justice's crucial role in our ability to heal. His work highlighted forgiveness as "the best form of self-interest" and said it’s not about excusing the past or erasing pain. It's about remembering and letting go of the need for vengeance, giving ourselves the freedom to heal.

A task that is easier said than done. As Alexander Pope’s line goes: "To err is human, to forgive divine."

Ignited by History is for curious people like you!

You can subscribe to my Substack for free to receive my next post directly in your inbox. Please share this with a friend who’s also lost sleep over something that happened hundreds of years ago…

References

Return to Macassar — A Japanese P.O.W. Camp Revisited After 50 Years (1992). A travel journal by Roger.

Falle, Sam. My Lucky Life: In War, Revolution, Peace and Diplomacy. United Kingdom, Book Guild, 1996.

Tutu, Desmond. No Future Without Forgiveness. United Kingdom, Ebury Publishing, 2012.